The Famine We Don’t See: Whose Suffering Counts in a Hierarchy of Death

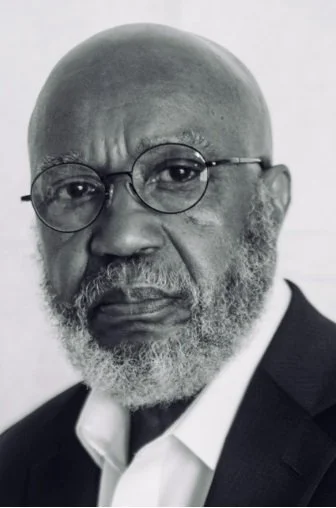

By Norman Franklin

Norman Franklin

Women and children are starving in Gaza. Their frail, skeletal images dominate headline news coverage. The famine-like crisis—strategically framed as a "food crisis"—threatens the lives of more than a million Palestinians.

But semantics don’t ease the intensity of their hunger. They don’t lessen the suffering. A famine is defined as an extreme scarcity of food. The emaciated bodies of elderly men, women, and children are living testimony to that reality. With no immediate end to the war in sight, the crisis has undeniably crossed the threshold into famine.

Gaza's humanitarian emergency has overtaken media coverage of the devastation in Ukraine. Meanwhile, the suffering in Africa and Haiti barely earns a passing mention—aside from the occasional, disparaging references to poor governance.

All are part of humanity’s suffering. All are newsworthy. Each crisis deserves empathetic acknowledgment from the 24/7 news cycle. Yet, the ideologically filtered nature of media coverage forces us to ask: what criteria do news editors use when deciding whose suffering is worthy of attention?

The crisis in Gaza has received exceptional global media coverage. In contrast, the long-standing crises in Haiti and parts of Africa have received far less attention—despite affecting larger populations and spanning decades. This disparity reflects what media scholars call a “hierarchy of death”—the notion that some lives are treated as more valuable than others in the global narrative.

Gaza's conflict is geopolitical: marked by mass displacement, military action, and international diplomatic debates. Haiti, by contrast, suffers under the weight of neocolonial legacies—its current crisis driven by gang-related violence, economic collapse, and rampant inflation. Nearly six million Haitians face acute food insecurity, with over two million experiencing IPC Phase 4—one step below famine. These conditions predate the crisis in Gaza by more than five years.

In Gaza, 111 deaths have been directly linked to famine-like conditions, with over a million facing acute food insecurity. Yet, across the African continent, famine has taken a far greater toll over a longer period. Between 1958 and 2000, eight major famine events were recorded, with durations ranging from one to seven years. The Democratic Republic of the Congo saw an estimated 2.7 million deaths: Ethiopia, 800,000. These famines were driven by war, conflict, political instability, and climate-related droughts. International aid efforts have been similarly uneven—and often undermined.

The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), once instrumental in famine early warning systems and humanitarian response, has been gutted by the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE). In January, DOGE canceled 90 percent of its agreements, citing the need to eliminate waste, fraud, and abuse. As a result, more than $8 billion in aid remained undistributed. The Office of Inspector General later reported that $489 million worth of food aid was at risk of spoilage due to halted operations and staff reductions.

The dismantling of critical infrastructure for humanitarian relief raises uncomfortable questions: Who decides which lives are mourned in public? Is the media driven purely by sensationalism—or by deeper biases, including the reluctance to acknowledge the ongoing impact of neocolonialism in Haiti and across Africa? In a world flooded with information, silence is not absence—it is a choice.