The Erie Canal and the Flight for Freedom

Many people learned about the Erie Canal in their school textbooks. The old song about the Erie Canal became part of many music classes. The song that described life along the Canal was written in 1905 under the title of “Low Bridge, Everybody Down.” This 363-mile waterway became a direct route from New York city to the Midwest resulting in large-scale commercial and agricultural development. It was the brainchild of New York Governor Dewitt Clinton, who was often ridiculed for what some saw as “Dewitt’s Folly.” The canal became a major transportation route for goods and people. The canal opened on October 26, 1825, with a caravan of ships led by the Governor. One fact left out of the lessons in school was that the Erie Canal played a major role in the freedom of fugitive slaves. It became an escape route for slaves fleeing the horrors of slavery in the south. They were brought into Buffalo under the cover of darkness.

Fugitive slaves traveled along the Erie Canal whose terminus was the commercial slip connecting it to the inner harbor in Buffalo, New York. Buffalo was the queen city of the Great Lakes, a place where canal boats, lake steamers, and later the railroad came together. The Erie Canal became part of the Underground Railroad, which was a series of safe places for fugitive slaves seeking freedom from oppression. Once fugitive slaves made it to Buffalo, they hoped for a better life. And like immigrants from other ethnic groups, the Erie Canal provided jobs for fugitive slaves. Many slaves helped to build locks in Lockport. They became stewards, cooks, waiters, and even firemen on the canal. One of the most well-known conductors on the Underground Railroad was an African American named William Wells Brown. He once had a home located at 13 Pine Street in the city. His home was located on the present site of the First Shiloh Baptist Church. There was a sign in front of the church indicating that this was his home. William Wells Brown escaped from slavery in Missouri in 1834. Brown made his way to Cleveland, then to Buffalo in 1835. As a crew member on a Lake Erie Steamer, he helped dozens of fugitive slaves escape to Canada. Later, as one of the nation’s leading anti-slavery activists, he wrote about the cruelty of slavery in America. Brown also became the first African American novelist in the country. You can see his portrait and bio on the Freedom Wall located on East Ferry and Michigan Avenue.

Another well-known African American named Walter Hawkins traveled along the Erie Canal to freedom. His story is written in a book published in 1891 called, “From Slavery to the Life of Bishop Walter Hawkins or the Life of Bishop Walter Hawkins written by Celestine Edwards. Bishop Hawkins traveled along the Underground Railroad and arrived in 1837. One of the chapters in the book specifically speaks of Buffalo. It describes the city as a busy commercial area in 1840. The author stated that Buffalo was a city where fugitive slaves could find work. Hawkins found a job as a waiter. He soon discovered that Blacks had no place to worship except in open fields or in houses. They were not allowed to worship with whites. Hawkins was determined to learn how to read and write. He spent evenings studying. His main goal was to learn how to read the Bible. He remained in Buffalo for about three year and during that time, he built the first Methodist church for Blacks in the city. Author Celestine Edwards noted the following: “By building a church for his race, he gave them their first lesson in the art of government, and to learn how to utilize their combined resources. He taught them that there is strength in unity.” Hawkins later married and left Buffalo to join his brother in Massachusetts.

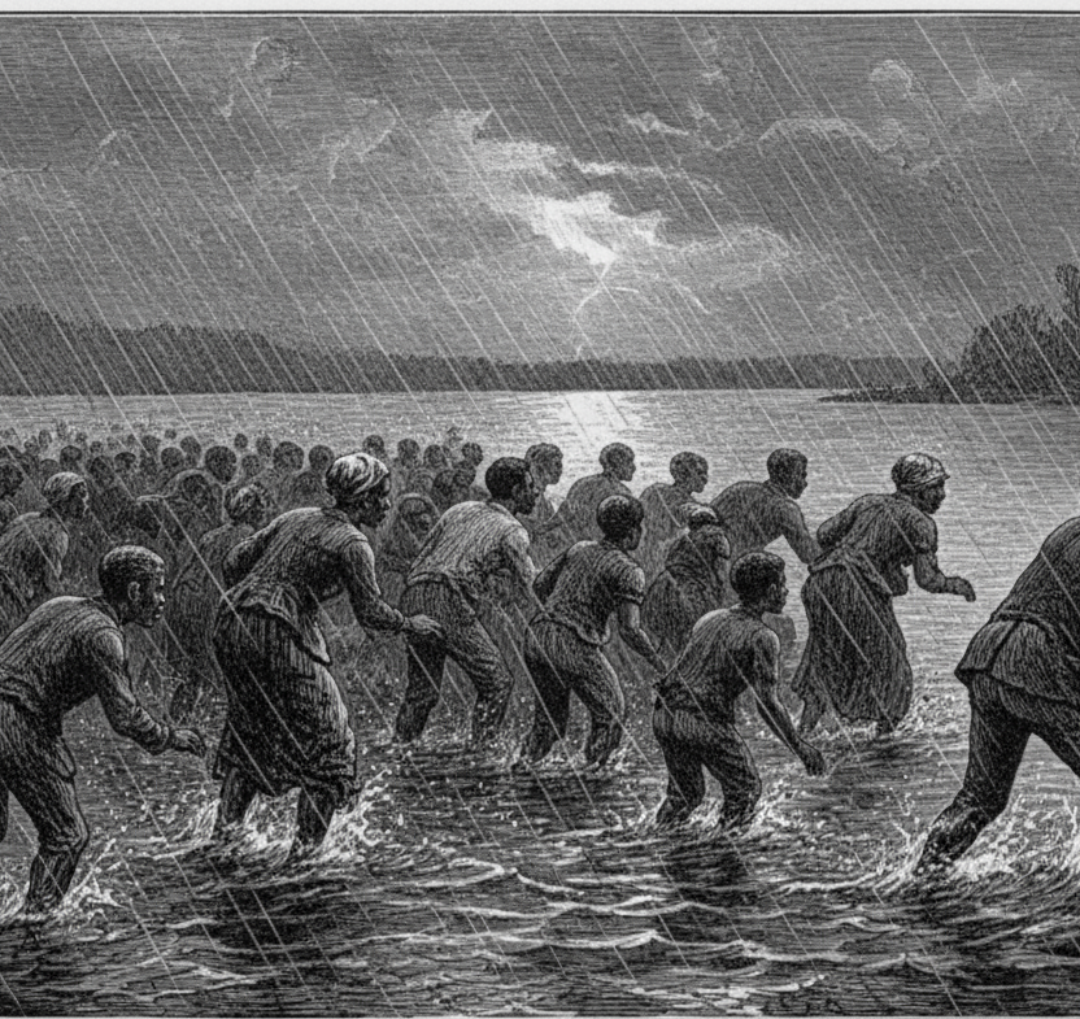

Harriet Tubman took many of her passengers through the Erie Canal towns of Syracuse, Weedsport, and Rochester, where sympathetic Quakers and abolitionists gave aid to the fleeing slaves. Tubman was known to enter Canada through Niagara Falls crossing the Niagara River. The passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 was the reason for the increased number of slaves seeking freedom. President Millard Fillmore, the 13th president of the United States, signed this law. Fillmore was also the first Chancellor of the University of Buffalo in 1846. The Fugitive Slave Law was known as one of the most inhume laws of the nation. Citizens could be fined $1000 for giving food and shelter to fugitive slaves, or face imprisonment. Slave catchers were also given the right to search private homes and return fugitives back to slavery. If they were caught they faced horrific beatings and mistreatment from their former owners. Severe punishments for slaves were described in many books. However, the Anti-Slavery Almanac of the early 1800’s describes the most horrific forms of punishment. The fear of being sent back south caused thousands of escaped slaves to flee to Canada.

There were incredible stories of escape along the canal. One such story involves a black man who had fled from his master and got a job working on one of the canal boats. When he saw his old master, he made his way under the dock, took another boat, and escaped. Entire families were able to escape. The goal of the fugitive slaves was always to reach what they called “the land of Canaan” or Canada, which was seen as a sacred land of freedom. It is estimated that over 40,000 slaves escaped to Canada by passing through Buffalo between 1830 and 1864. Some historians point to Africans settling here even before these dates. The formation of abolitionist and anti-slavery societies as well as the presence of religious groups contributed to the success of the Underground Railroad in Buffalo and Western New York.

As we observed the two hundredth anniversary of the Erie Canal, we must include the history of African Americans and how the Erie Canal was used in the fight for freedom. Slaves traveled through Black Rock, Batavia, Lockport, Lewiston, and Fredonia. Their stories need to be told, and all Americans need to be exposed to this history!! References for this article can be found at the Buffalo History Museum and the Buffalo and Erie County Public Library.