Black Christian Genius and the Truth America Resisted

by Norman Franklin

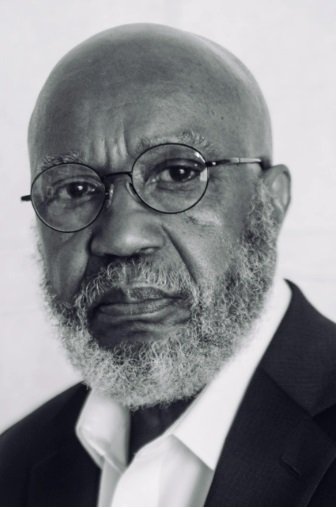

Norman Franklin

There is little question that in this second decade of the twenty-first century, faith has moved from the churches on the corner to the center of headline news and political identity. By 2025, religious identity reached a fever pitch. What was once personal conviction became weaponized religion and performative politics—faith bent toward power rather than truth.

The marriage between Christian ity and politics has fused the nation and religion into what is now widely recognized as Christian Nationalism. This condition didn’t evolve in a vacuum. Black theologians have warned of this malignancy for centuries. They spoke prophetically. White America, with self-appointed normative author ity, dismissed their witness. Could this morass of harsh Christian governance, underpinned by errant theology, have been avoided? Is the African Ameri can theological voice not credible?

February is Black History Month. It is an opportune time to examine—and recover—Black Christian genius. The Rev. Hosea Easton, a free Black man, spoke these words in 1837: he said, “The spirit of slavery will survive in the form of racial prejudice, long after the system of slavery is overturned. Our warfare ought not be against slavery alone, but against the spirit which makes color a mark of degradation.” Chattel slavery thrived for another quarter century after this prophetic warning.

There are two things to note about Easton’s genius. One, he recognized that the oppressive system was antithetical to the God he served. Two, he named the cancer festering in the bowels of America— whiteness.

Whiteness is a constructed social and theological framework that emerged in the modern Atlantic world to assign moral innocence, cul tural normativity, and divine favor to European-descended identity, while marking non-European peoples as deficient, dangerous, or expendable. Whiteness is not an individual; it’s a pernicious and pervasive system that has a stranglehold on America’s social, religious, and political life.

Dr. Martin L. King, Jr., the martyred twentieth-century prophet, spoke to the white church, which was more concerned about order than justice. His nonviolent strategy seared the conscience of America, and he challenged government to make good on its promise of equality, life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for all its citizens.

In his Letter from the Birmingham Jail, King challenged the theological posturing of progressive white churches. King said, “I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate.” There was a paternalism problem—we are with you, brother was their spin on his civil activism, but be patient; now is not the best time.

There are a plethora of other Black intellectuals and theologians who warned America of its misguided social policies, religious exclusions, and politics for the privileged.

I’ll name a few: Frederick Douglass, abolitionist, orator, and preacher; Langston Hughes, poet and social advocate; James Baldwin, author, essayist, and social critic; Rev. Gard ner C. Taylor, renowned pastor and theologian; Rev. Howard Thurman, author of Jesus and the Disinherited; and James Cone, father of Black The ology. All Black intellectuals, Black theologians, Black genius—dismissed by the normative culture: social, aca demic, religious, and political.

They each used their voices and their platforms to warn America of the dichotomy between the Jesus of America and the Jesus of the Bible. In “Jesus in Texas,” Hughes portrays Jesus as a brown-skinned immigrant who shows up in a Texas town. His difference in person, color and identity challenges the social order. He is jailed. The irony is that Black and brown-skinned Imago Dei are devalued, demonized, seized, jailed, and deported in America’s cities today.

James Baldwin didn’t reject Jesus— he rejected white Christianity because it lied about love, about innocence, and about the conflation of religion and power.

James Cone, viewed by normative theological spaces as controversial and radical, likened the lynching tree to the cross. For Cone, the crucifixion only makes sense when read through the lens of the oppressed. Cone would say that if Christ appears among the undocumented, detention is not a failure of Christianity—it is Christianity as practiced by empire.

“Between the Christianity of this land and the Christianity of Christ, I recog nize the widest possible difference—so wide that to receive the one as good, pure, and holy is of necessity to reject the other as bad, corrupt, and wicked.” —Frederick Douglass